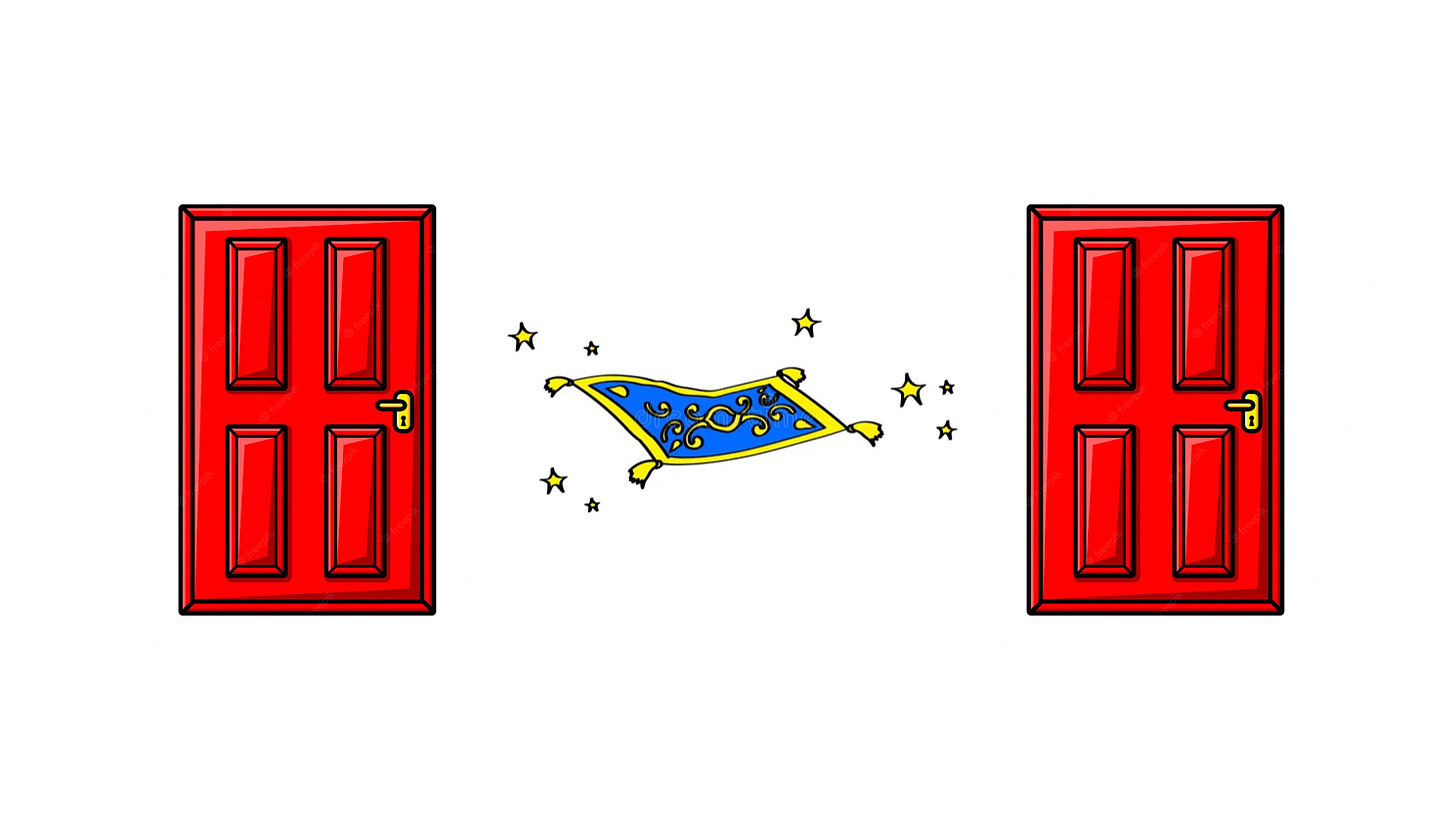

[The Art] Door—Magic Carpet—Door

A proven framework for keeping readers engaged (Fiction & Nonfiction).

“A woman opens a door. She walks across the wooden floor. She opens the next door and continues on.”

These 3 sentences tell an entire story.

It’s not a particular engaging story, but it’s a “story” nonetheless—because it has a beginning (a woman opens a door.), a middle (she walks across the wooden floor—clearly trying to get somewhere.), and an end (she opens the next door—closing one chapter and beginning another). We could say this is sufficient in completing an arc, or even a Hero’s Journey.

The question is: “How do we make it better?”

First, we need to start by acknowledging: “Better” is a misleading word.

When we tell ourselves we need to make something “better,” we begin from a place that assumes the scaffolding of the thing we are trying to improve (be it a single sentence or an entire idea) is sturdy—we just need to make it “sturdy-er.”

I wrote about this same idea, applied to business, with Category Pirates back in 2021: The “Better” Trap.

If we begin the brainstorming process from this place, what happens is we begin to imagine all the ways we can make the middle (the floor, in this example), incrementally better.

And how might we do that?

Maybe the floor should be linoleum instead of wood.

Maybe the floor should be shiny instead of dull.

Maybe the floor should be expensive instead of cheap.

Maybe the floor should be brown instead of that ugly, disgusting yellow.

And so on—which is where most writers spend their time: swapping out adjectives and descriptions with the hopes of making their work better.

The problem is… do any of these changes really “improve” our story?

Sure, they might be “better” descriptions that what currently exists—but the question to ask is: “What if what I currently have doesn’t need improving?”

Which leads us to the deeper question:

“What if I need something DIFFERENT?”

Aha!

Chances are, the first version of your story (any story) is mediocre. And the part that is most mediocre probably isn’t the beginning or the end (the doors), but the middle (the floor between them) and the journey that happens between points A and B.

But “mediocre” is lazy, subjective language. Let’s be more precise.

Chances are, the first version of your story (any story) is expected or predictable.

If it is a love story and Door A reveals the leading lady to be a boy-crazy blondie, we “expect” she will fall in love with the first warm body who makes her blush on the street (The Floor). When this happens, they will live happily ever after (Door B).

If it is a mystery story and Door A reveals a fidgety, guilty looking chef standing over a dead man on the floor, while holding a knife, we “expect” him to be the killer (The Floor). When he is found guilty, he will go to jail and the restaurant will return to normal (Door B).

And if it is a corporate presentation and Door A reveals the problem in the software industry is “finding talent,” we “expect” the solution to be an easy but likely predictable way of finding talent—like hiring a reliable recruiting firm (The Floor). When the talent is found, and the role is filled, the company is successful (Door B).

Which means you, as the writer, have a very persnickety job to do.

You must take your reader from Door A to Door B without succumbing to what is “expected,” but also without taking the reader somewhere they cannot (and will not!) “expect” to go—in the context of the story.

George Saunders explains this concept in his book, A Swim In A Pond In The Rain.

On page 22, in dissecting Anton Chekhov’s short story, “In The Cart,” he explains: “Which of your ideas feel too obvious? That is to say: Which, if Chekhov enacts them, will disappoint you by responding too slavishly to your expectations? (Hanoi, on the next page, drops to one knee and proposes.) Which, too random, won’t be responding to your expectations at all? (A spaceship comes down and abducts Semyon.) Chekhov’s challenge is to use these expectations he’s created but not too neatly.”

A challenge, no doubt!

So, let’s use a framework:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Art & Business of Digital Writing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.