Dear Writer,

What Is A Book Title?

It’s such a simple question, and yet most writers never ask it.

Instead, they rush into brainstorming title ideas, finding “comp covers,” or trying to create the perfect pun.

But in its simplest form, the title of your book isn’t actually a title—or a “bow” you tie on top of your work before you present it to the world. It’s also not just a sales pitch for the pages of content inside.

A book title is more like a sliver of real estate in your target reader’s mind.

When a book already exists on a topic, and you decide to write a book that is going to be “better” than that book, you’re competing for existing real estate. And the more books that already exist on a given topic, the more competitive the market. Think of yourself like a little real estate developer who just moved to New York City with dreams of building an empire. Can it happen? Sure—others have. But are the odds in your favor? Eh, probably not.

When a book hasn’t yet been written on a topic, and you decide to be the first, you’re no longer competing for existing real estate in the target customer’s mind. In fact, depending on how “early” you are, there might not even be a market. You have to create it—which is both the opportunity and the burden. It’s a burden because there aren’t readers actively searching for that topic (yet). But it’s an opportunity because if you can create the market, you can own it—or own a meaningful piece of it. To stick with the metaphor: instead of competing for real estate in New York, you’re building a new city (and new housing within that city) in the middle-of-nowhere Montana.

Unfortunately, most writers don’t think about their writing this way

It’s much easier to just wake up in the morning, pull the shades apart, stretch your arms big and wide, and say, “I’m going to write a book!” And then as long as your work appears somewhere in the world, well, you did it.

(Just know most, if not almost-all of these writers are broke.)

Which is why I’m going to help you not-think this way!

And give you a framework for The Perfect Book Title.

Title-First vs Title-Last

Conventional wisdom says, “Just start writing and the title will reveal itself at the end.”

This is what most big publishers say to their writers.

The problem with this Title-Last approach is it severely misunderstands the impact a title & subtitle can have on the content.

For example, look at the following (made up) main titles & subtitles:

Flow State: How To Get In The Creative Zone

Flow State: How To Get In The Competitive Zone

Destroying Flow State: 8 Bad Habits That Crush Your Productivity

Destroying Flow State: The 7 Ways People Self-Sabotage Their Creativity—And How To Overcome Them

To the untrained eye, the above 4 titles are just “different variations of the same idea.” But that couldn’t be further from the truth. These are not 4 different title options. These are actually 4 different books, that make 4 different promises, that will attract 4 different types of readers, that will produce 4 completely different types of content:

Title #1 is a “How To” book (so it would most likely be structured in “Steps”), and those “Steps” will be tailored specifically to “creativity.”

Title #2 is also a “How To” book, and would also be structured in steps, but will be tailored to a completely different audience & outcome.

Title #3 is not a “How To” book, and it’s also not an aspirational book. It’s a cautionary tale, and anchored to a specific number of bad habits that lead to negative outcomes for the reader.

And Title #4 is also not a “How To” book. It’s not promising “steps” or anything actionable. It’s promising “ways,” which means its promise is to help the reader understand, not “do.”

The title is what decides the entire direction of the book.

Whereas the book isn’t what decides the direction of the title.

My recommendation:

If you are serious about being a serial author (as in you want to write many books), I would strongly encourage you to build the skill of taking a Title-First approach. And if you have to “start writing” to figure out what your book is about, that’s fine—but commit to a direction as quickly as you can.

Because…

The longer you postpone committing to a title, the longer you're going to struggle to know what your book is truly about…

The less clarity you’re going to have on the promise you’re making to the reader (and whether you’re delivering on that promise in the content)…

The less likely readers are to understand what your book is about, and whether what you’re promising to them is worth their time…

The fewer people will buy your book.

It’s all connected.

For example, there’s a reason why MrBeast requires his team to come up with the perfect thumbnail and title before investing millions of dollars into producing their next YouTube video. Because the positioning of the idea and the title is what dictates the content.

I firmly believe every writer should spend a disproportionate amount of effort stress-testing their book title and the positioning of their idea before they even begin writing.

Here’s how:

The 7 Categories Of Non-Fiction Best-Selling Books

Before you begin writing your book, wouldn’t it be helpful to know which categories of non-fiction books tend to produce the best results?

In my book, Snow Leopard, we conducted a study of the best-selling business books over the past 20 years, organizing them by category. And we found that almost all of the Top 444 best-selling business books of the past 20 years can be organized into these 7 buckets:

Personal Development

Personal Finance

Insights/Thinking

Leadership

Case Study/Allegory

Functional Excellence

Relationships

And even within these 7 buckets, the top 2 (Personal Development and Personal Finance) are the largest.

This is not an accident.

Something I learned very early writing on Quora was: the size of the question dictates the size of the audience. Which means in order to reach millions of readers, or write a book that unlocks millions of dollars in revenue, you need to answer big, universal questions that speak to the widest number of people. And what are the 2 largest questions?

“How do I improve myself?” (Personal Development)

“How do I make more money?” (Personal Finance)

If you don’t speak to one (or both) of these mega-categories of interest, it doesn’t matter how “good” your book is—the question your book is answering doesn’t have enough scale. There literally aren’t enough readers who would be willing to consume your product.

So, congratulations… you want to write a non-fiction book!

Well, unless you’re just writing for yourself and don’t care what the outcome is or how many people buy it (which a lot of people say but is never the truth—they always come back around a month later going, “How can I make my book sales go rocketship?!”), you should work in reverse:

What are your external expectations? How many copies are you aiming to sell? How “big” would you like your book to try to be?

And does your idea sit within in a mega-category where those expectations are not only possible, but realistic?

If not, you either need to a) write the book you want to write but reframe your expectations, or b) change the book you want to write to have a better chance at meeting or exceeding your expectations.

Personal Credibility or Borrowed Credibility

The next big thing you need to decide is whether your book is going to lean on Personal Credibility (you have achieved something noteworthy yourself) or Borrowed Credibility (curating insights from other relavent, noteworthy people).

For example:

Ray Dalio’s Principles: Life and Work (horrible subtitle) leans heavily on Personal Credibility. Why would you want to know Ray Dalio’s principles for life and work? Well, because he’s a billionaire. That’s why.

Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle Is The Way: The Timeless Art Of Turning Trials Into Triumph (nearly perfect book title) leans heavily on Borrowed Credibility. Ryan isn’t telling you “his” framework for turning trials into triumph. He’s telling you Marcus Aurelias’s philosophy on stoicism, and then borrowing other successful people’s credibility and stories to reinforce it: John D. Rockefeller, Amelia Earhart, Ulysses S. Grant, Steve Jobs, etc.

To be clear: this isn’t a decision as to whether your face should be on the cover, or the font of your name should be even bigger than the title. In fact, from our best-selling non-fiction book study in Snow Leopard, we actually found that Idea-Forward ideas, titles, and covers almost always outperformed Author-Forward ideas, titles, and covers (giant celebrities being the exception to the rule). 99% of the time, you are better off positioning your idea first and your credibility second.

Still, the decision of Personal Credibility or Borrowed Credibility is important because it impacts how you are going to deliver on the promise of your title. If it’s Personal Credibility, you should lean on personal stories & insights. Whereas if it’s Borrowed Credibility, you should lean on curated stories & insights.

The mistake writers make here is when they don’t have clarity over which type of credibility their book is using (or needs for the idea they’ve chosen), and then fail to deliver on that promise to the reader. For example, imagine if you bought Ray Dalio’s Principles because you were excited to learn “his” principles for life & work… only for him to share almost nothing of his own, and instead tell you stories about George Washington and Bill Gates’ principles for life & work.

You would be very disappointed!

Timely or Timeless

The last big strategic decision you need to make is which type of book you’re writing:

A Timely Book… to take advantage of an opportunity-now.

A Timeless Book… to take advantage of an opportunity-later.

Generally speaking, “timely” books tend to make more money in the short term. This is because timely books speak to pre-existing problems or desires (aka markets). For example, if you wrote a book about how to get started with Kindle publishing back in 2008, you crushed it (and probably make millions of dollars) for a short period of time. But chances are today, almost two-decades later, that original book probably isn’t relevant anymore (the information is outdated) and doesn’t make any money. Very timely, not very timeless.

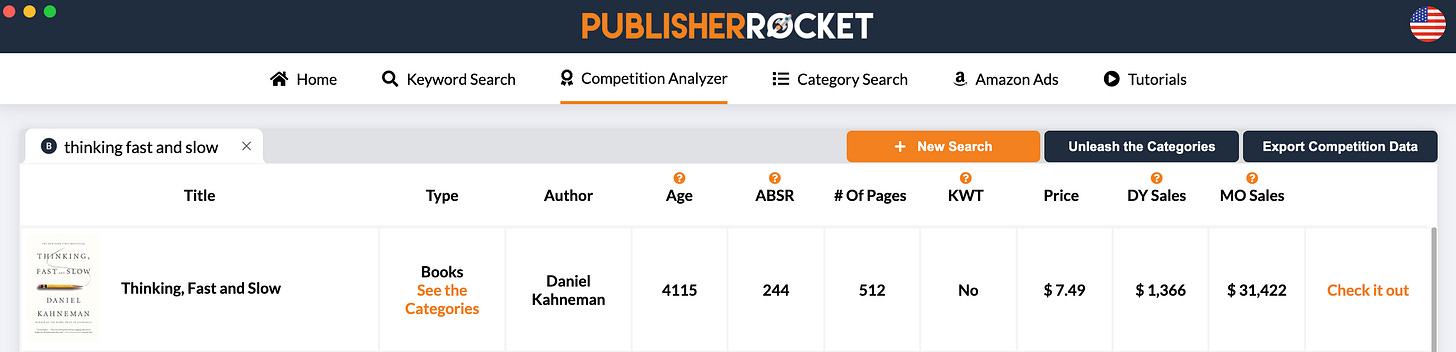

“Timeless” books, on the other hand, tend to make less money in the short term but can make way, way more money over the long term. The book, Thinking, Fast and Slow is a good example. This book came out in 2013 and it’s still selling well over a decade later.

Data pulled from PublisherRocket (Print Books / eBooks / audio books):

If we look back at the 7 non-fiction mega-categories, some are inherently better suited for “Timely” books—and others, “Timeless” books:

Personal Development: Could be either, so better to lean Timeless.

Personal Finance: Could be either, so better to lean Timeless.

Insights/Thinking: Typically Timely (most data/insights get outdated within a decade).

Leadership: Could be either, so better to lean Timeless.

Case Study/Allegory: Typically Timely (most case studies/allergies get outdated within a decade. The book Good To Great comes to mind here. Extremely relevant and a huge best-seller in the 2000s. Today, almost completely irrelevant.)

Functional Excellence: Typically Timely. Functional Excellence is a fancy name for “How To,” and most “How To” books (especially involving technology) get outdated within 5 years or less.

Relationships: Could be either, so better to lean Timeless.

So again, depending on which type of book you want to write, it’s crucial to know whether your book even has Timeless potential—or if it’s more of a Timely “cash-grab” (which is fine, just don’t confuse the two).

Some good rules of thumb…

If you are writing a Timely book:

Use Timely (even trendy) stories, case studies, data, etc. There’s a reason so many non-fiction books lean on “ground-breaking research.” Readers like to feel like this data, or these insights, “just came out.”

Use Timely credibility (Personal or borrowed) that is highly relevant to the topic. Using “timeless” credibility from 20+ years ago doesn’t work as well for Timely topics. Readers want to know you, or someone else, was JUST successful using this information recently.

Make the content as actionable as possible. Because what people are really buying is immediate “How To” information.

If you are writing a Timeless book:

Use Timeless stories/insights/allegories, and deliberately avoid Timely case studies, data, or stories tied to Timely events. For example, in Good To Great, Circuit City was hailed as a success story. Less a decade later, it filed for bankruptcy and was no longer relevant. So even if insights from the company’s success are “Timeless,” they’re hard to read today because they were anchored to a Timely case study.

Over-rotate on “thinking/principles” and avoid prescriptive “How To” information. The more you lean into “How To” do something, the more Timely your book becomes. Whereas the more you lean into “Timeless principles” that could be applied across generations, the more Timeless your book becomes.

Avoid generation-specific language. If your book (especially the title) leans on “trendy” language, that is going to work really well in the short term and then age very poorly over the long term. The book #GIRLBOSS by Sophia Amoruso is a great example. Including a hashtag in the title when it was published in 2014 was hyper-relevant—and the book became a New York Times best-seller. Today? That hashtag feels outdated and irrelevant, and the book with it.

Some data to support: #GIRLBOSS as a print book is averaging ~$173 in sales per month on Amazon today.

To recap:

These are the strategic decisions you need to make before you even start thinking about how to “position” your idea:

Are you taking a Title-First approach? (The answer should be “Yes.”)

What are your expectations for external outcomes? And are you writing a book in one of the big 7 non-fiction mega-categories?

Are you leaning on Personal Credibility or Borrowed Credibility?

Are you trying to write a Timely book or a Timeless book?

You need to answer these questions, first.

Then, you can begin the game of properly positioning your chosen idea in the mind of your target reader.

Tactically, here’s how to do that:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Art & Business of Digital Writing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.